What Makes a Great Founding Team?

August 15th, 2023

My son recently asked me, “Dad, what makes a great founding team?” Gabriel is a Junior in high school and very interested in entrepreneurship. He’s really “hungry” to build “something,” but determined to build on what he’s learned growing up in an entrepreneurial home. In fact, he has a really interesting idea in Applied AI. He’s currently proving it out in code, and a friend of his has expressed an interest in working on it with him. So it’s a great question. It's a relevant question. It’s a hard question. My views on the answer continue to take shape. There is a lot of thought-leadership on this subject out there so I'll try not to regurgitate it. I’ll simply tell you what I told him. These are things that I’ve learned; things that I “continue” to learn - and sometimes painfully.

My son recently asked me, “Dad, what makes a great founding team?” Gabriel is a Junior in high school and very interested in entrepreneurship. He’s really “hungry” to build “something,” but determined to build on what he’s learned growing up in an entrepreneurial home. In fact, he has a really interesting idea in Applied AI. He’s currently proving it out in code, and a friend of his has expressed an interest in working on it with him. So it’s a great question. It's a relevant question. It’s a hard question. My views on the answer continue to take shape. There is a lot of thought-leadership on this subject out there so I'll try not to regurgitate it. I’ll simply tell you what I told him. These are things that I’ve learned; things that I “continue” to learn - and sometimes painfully.

Aligning incentives among co-founders.

First, I would say that no two founders will share exactly the same motivations, even if they can - and must - share the same business objectives. That might sound counterintuitive, right? Don’t all founders want to make a lot of money together, thumb their noses at day jobs and corporate bosses, pat each other on the back for their ingenuity, and ultimately retire on a beach to sip piña coladas? Well, first-time founders might think this way. Those of us who have been out there for a while - and our spouses and children - know that the reality is quite different. It’s not glorious. It’s damn hard. It usually takes years, and during that time, co-founders and their situations can change. Add to this the sobering reality that 80 to 90 % of startups fail, and if you finally do succeed, then you're probably going to be playing some financial catch-up and wondering, “Okay, now what?” In fact, if you have any doubt that all co-founders share similar expectations for the arduous road ahead and are able to plan for - and endure - the worst, then just stop. Don’t do it. It should follow, then, that co-founders must share the same motivations in order to succeed, right? Not exactly. I've learned that you must seek to fully “understand,” but not necessarily "share," the motivations of your potential business partners and they must understand yours. It’s okay that motivations turn out to be different so long as they can be “aligned.” If you can understand what “really” motivates each other to achieve a common business objective together, then you can perhaps begin to constructively align (and realign) the incentives that drive you both. Money is only one driver, and it’s important to dig deeper to understand what that money really represents in your potential co-founder’s mind... Is it to “keep up with the Joneses” or is it to afford school tuition to better their children’s opportunities in life. Is it to have more flexibility to be present at home than a desk job? Does it satisfy some other personal "growth" goal? Can you be “honest” with one another about what really drives you to achieve that common business objective? Are they good and respectable reasons? Are they achievable? Another word for “motivation” is perhaps “passion” or, at least, motivation hints strongly at the notion of having and demonstrating a passion. You each benefit by appealing to and promoting the other’s “personal” passion. I often now say that I want to attract key people to my team who know - with confidence - that they have no limit to the financial gain and position to which they can aspire on their own merits... And, that anyone unwilling to do and extend the same - and who, thus, does not value the same - must be avoided. Can you align incentives among co-founders?

Stating the primary motivation for having a business together.

To carry the first argument a bit further, there are two primary motivations for being in business together, and I believe that all personal motivations must align to one or the other: A Long-term Equity Play or a Lifestyle Play. A “long-term equity” play means that you’re signing on for typically a 5-7 year uphill battle for a large liquidity event that makes all of the sacrifice worth it in the end. On the other hand, a “lifestyle” play is where you’re less concerned about a later exit, and more interested in providing the type of life that you want along the way, i.e., with some toys and perks. Past the point of coming up with a business idea and doing some discovery that suggests that people will want what you offer them, you should be considering if the model is “repeatable” and if it is “scalable.” These are different. If you sell something to someone, can you “repeat” that with some viable predictability? Whether you are pursuing a long-term equity play or a lifestyle play, your business model must be “repeatable.” Your business is considered “scalable” if you can “grow it.” Scalability might be less of a concern in a lifestyle play. Your founding team might have a bank of business and never really need to grow it beyond yourselves to continue the desired lifestyle. However, if you are seeking any kind of investment capital, you need to demonstrate “scalability.” It’s always a far better argument when raising money that you need it to simply add more fuel to an existing fire - and by fire, I mean high demand for rapid growth. Raising money and having investors who expect “growth” and a return on their investment adds a lot of stress. Is everyone signed on for that kind of stress? There is nothing wrong with a lifestyle play, and it is entirely possible that it “could” be scalable if you choose to grow it beyond yourselves later to achieve some kind of liquidity event. So, do the personal motivations of co-founders align better with a long-term equity play or a lifestyle play?

Agreeing on what you’re going to build, how you’re going to prove Product-Market Fit, and understanding your collective tolerance for pivots.

This is a tough one. It seems obvious, and yet co-founders (and yes me), can find themselves in business together, seemingly on the road-to-nowhere, but burning precious fuel nonetheless. Serious questions need to be asked and appreciated... What exactly are you going to offer and to whom? How are you going to objectively prove that people want it? A reply like, “I know they want it because I’m from the industry,” should be tested. Assumptions should always be tested. How are you going to get a working model that proves minimum viability? If your Minimum Viable Product (MVP) doesn’t seem to prove the right Product-Market Fit exists, what then? How much money have you already burned? Did you learn enough to tweak the model and test a new assumption? Can you afford to? Have you found that you've prescribed a “vitamin” when you thought it was a “painkiller?” Serious buyers want to kill a pain. Are you and your co-founders willing and able to pivot entirely if that’s what the market says to do? In other words, just how damn stubborn are you and your co-founders? Being “stubborn” and being “committed” are two different things. How do you know the difference? Can you get and accept the outside advice of mentors? Trust me, you need a co-founder with domain knowledge from within the reachable market, but “everyone” must be willing to adapt to the evidence, and sometimes that evidence can be quite different than what the team domain expert believes. If you cannot define together an MVP that is truly “minimal” in nature and how you’re going to test your assumptions as cheaply and quickly as possible, then take a step back. Further still, it’s not enough that co-founders nod their head in affirmation of a pivot - they have to believe it and act it out immediately and intentionally. Otherwise, resentment can grow behind the scenes.

This is a tough one. It seems obvious, and yet co-founders (and yes me), can find themselves in business together, seemingly on the road-to-nowhere, but burning precious fuel nonetheless. Serious questions need to be asked and appreciated... What exactly are you going to offer and to whom? How are you going to objectively prove that people want it? A reply like, “I know they want it because I’m from the industry,” should be tested. Assumptions should always be tested. How are you going to get a working model that proves minimum viability? If your Minimum Viable Product (MVP) doesn’t seem to prove the right Product-Market Fit exists, what then? How much money have you already burned? Did you learn enough to tweak the model and test a new assumption? Can you afford to? Have you found that you've prescribed a “vitamin” when you thought it was a “painkiller?” Serious buyers want to kill a pain. Are you and your co-founders willing and able to pivot entirely if that’s what the market says to do? In other words, just how damn stubborn are you and your co-founders? Being “stubborn” and being “committed” are two different things. How do you know the difference? Can you get and accept the outside advice of mentors? Trust me, you need a co-founder with domain knowledge from within the reachable market, but “everyone” must be willing to adapt to the evidence, and sometimes that evidence can be quite different than what the team domain expert believes. If you cannot define together an MVP that is truly “minimal” in nature and how you’re going to test your assumptions as cheaply and quickly as possible, then take a step back. Further still, it’s not enough that co-founders nod their head in affirmation of a pivot - they have to believe it and act it out immediately and intentionally. Otherwise, resentment can grow behind the scenes.

Having the right mix of skills and domain knowledge.

Again, this one seems obvious, but this too can prove difficult to discern. There’s always a bit of a leap of faith involved when you choose co-founders, but remember that CVs are pieces of sales literature for employers and recruiters. You should bring in the skills that you need only as you identify the need for them. You cannot have a co-founder just “waiting in the wings” to do their part when the time comes, i.e, when the product is “finished.” Co-founders must have and demonstrate the right skills and domain knowledge to immediately begin testing their assumptions and building the business “together,” hand-in-hand. The efforts of each must be immediately visible, understood, and fully appreciated. The best founding teams are gathered together in one, cheap room from sun-up to sun-down. You will identify the need for other high-skilled and talented people as you test assumptions and discover themes… You will likely not have the money to pay for them. You can attract entrepreneurial people who think like founders and demand less salary with an equity preference, but consider doing so on a vesting schedule as “equity compensation.”

Accepting and finding a path forward under a theory of constraints.

Everyone needs to be realistic about constraints. Constraints should be discussed routinely. You cannot “believe” a constraint into oblivion. I am a firm believer in the Power of Positive Thinking, but you can think positively about how to “deal” constructively with a constraint that isn’t going away any time soon. In my experience, dealing with constraints is an activity that is best suited for a team of three or more. With two co-founders, no one exists to break a stalemate when the constraint is recognized by both, but very different thinking between the two co-founders emerges. Likewise, two co-founders typically result from an existing relationship, i.e., a friendship. Sometimes, one co-founder will simply default to the other or not voice real concern out of a fear of disappointment and hurting the relationship. This is a fallacy - the stakes are simply too high for both of you to not fully engage each other in discussion and debate. Any time that you can get an objective, third or fourth party’s appraisal of your situation, you should do so. Likewise, it’s good to have others who can kindly “remind” someone of the history of a prior discussion. The biggest constraint most of us face is “money.”

Everyone needs to be realistic about constraints. Constraints should be discussed routinely. You cannot “believe” a constraint into oblivion. I am a firm believer in the Power of Positive Thinking, but you can think positively about how to “deal” constructively with a constraint that isn’t going away any time soon. In my experience, dealing with constraints is an activity that is best suited for a team of three or more. With two co-founders, no one exists to break a stalemate when the constraint is recognized by both, but very different thinking between the two co-founders emerges. Likewise, two co-founders typically result from an existing relationship, i.e., a friendship. Sometimes, one co-founder will simply default to the other or not voice real concern out of a fear of disappointment and hurting the relationship. This is a fallacy - the stakes are simply too high for both of you to not fully engage each other in discussion and debate. Any time that you can get an objective, third or fourth party’s appraisal of your situation, you should do so. Likewise, it’s good to have others who can kindly “remind” someone of the history of a prior discussion. The biggest constraint most of us face is “money.”

Knowing when bootstrapping must end for pre-seed to begin.

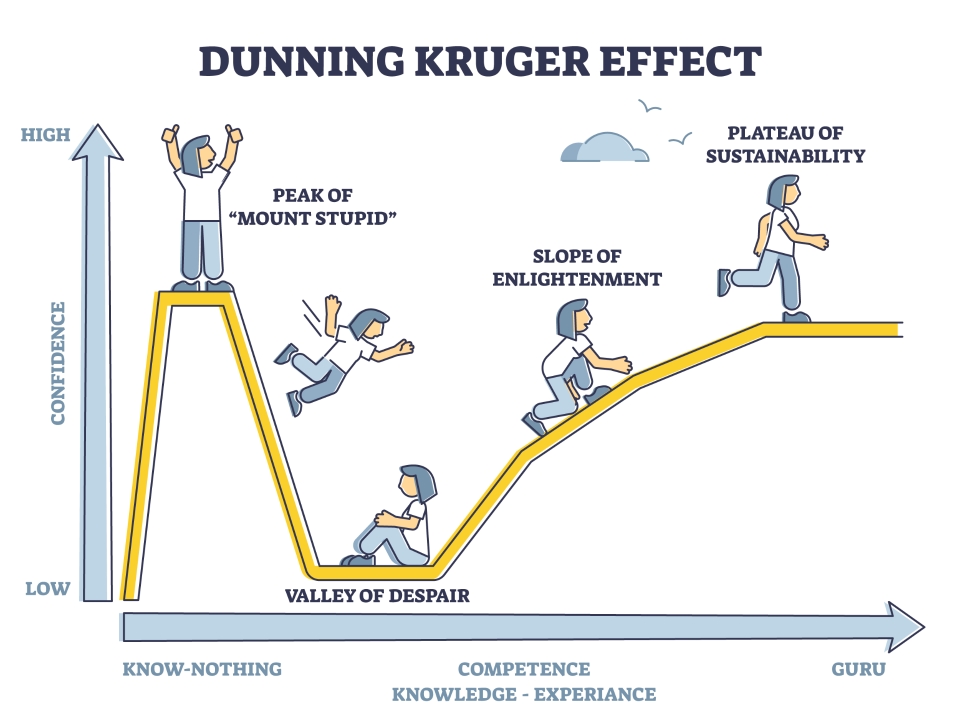

Things are typically great when you’re in the idea stage. It’s exciting. It’s a “high.” If you’re not familiar with the Dunning Kruger Effect, then I recommend that you study the model together. Building a business together means that you’re building “competencies” together and that usually involves hitting a low point and working your way up. Until you’ve achieved some level of market validation with paying customers, you will be engaged in “some” level of bootstrapping (spending your own money). If you want to pursue a lifestyle business, or think that you can fund a long-term equity play organically to the point of profitability (good luck), then you get to hold onto more equity. But remember this: You can own 100% of a company worth $0.00 and your equity is still worth $0.00. Likewise, if you and your co-founder have a 50/50 split on equity, but your partnership falls apart over money and sweat contribution arguments, then you both have 50% of nothing but grief. Establishing when the right time to fundraise begins should be well-discussed as early as possible, and it should almost always be driven by comparable benchmarks and norms, guided by sound startup principles. Y Combinator is a great resource to reference. Seeking some mentorship by people who invest in startups - even before you’re ready to fundraise yourself - is great. They can help you understand the right timing, might invest themselves, and can help you set a trajectory for future raises with the right milestones. It also might help level-set expectations among co-founders for when the idea has become viable for an outside investment. You or a co-founder may believe it's ready for an investment well before it actually is or vice-versa.

Things are typically great when you’re in the idea stage. It’s exciting. It’s a “high.” If you’re not familiar with the Dunning Kruger Effect, then I recommend that you study the model together. Building a business together means that you’re building “competencies” together and that usually involves hitting a low point and working your way up. Until you’ve achieved some level of market validation with paying customers, you will be engaged in “some” level of bootstrapping (spending your own money). If you want to pursue a lifestyle business, or think that you can fund a long-term equity play organically to the point of profitability (good luck), then you get to hold onto more equity. But remember this: You can own 100% of a company worth $0.00 and your equity is still worth $0.00. Likewise, if you and your co-founder have a 50/50 split on equity, but your partnership falls apart over money and sweat contribution arguments, then you both have 50% of nothing but grief. Establishing when the right time to fundraise begins should be well-discussed as early as possible, and it should almost always be driven by comparable benchmarks and norms, guided by sound startup principles. Y Combinator is a great resource to reference. Seeking some mentorship by people who invest in startups - even before you’re ready to fundraise yourself - is great. They can help you understand the right timing, might invest themselves, and can help you set a trajectory for future raises with the right milestones. It also might help level-set expectations among co-founders for when the idea has become viable for an outside investment. You or a co-founder may believe it's ready for an investment well before it actually is or vice-versa.

Cultivating a harmonious coordination of efforts.

One of my favorite classical business texts was written by Napoleon Hill. If you’re unfamiliar with the author, I suggest you look him up. The philosophy he describes has been rewritten with varied terms and new, modern spins ever since. One thing he hits on that I have truly come to appreciate - and that now predicates any business partnership that I might consider - is the likelihood of preserving “a harmonious coordination of efforts.” This is tough. Disagreements will arise. This can be very healthy. A compromise found somewhere in the middle, after all opinions have been heard and weighed, is usually the best solution to a problem. As in marriage, you are going to have clashes between logic and emotion. Neither are wrong on their own, and both should be heard. As in politics, you are going to have clashes between conservative and liberal views. The answer is in the middle. If you ever visit France, you will see the following words just about everywhere: Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité. I remember watching President Macron describe what this means to a group of French school children, and his presentation stuck with me. He said something like this: The conservative “Right” is, has been, and always will be concerned with “Freedom” - Liberté at all costs. The liberal “Left” is, has been, and always will be concerned with “Equality” - Égalité - above all else. Neither stance is bad. But how do you keep people from tearing each other apart in society? Fraternité. Brotherhood and sisterhood. Never forgetting the person. Never forgetting the neighbor. Never forgetting to pursue civil discourse. Always seeking to preserve a “harmonious coordination of efforts.” Is your potential co-founder a hothead? Can you reason well together? Does a better outcome emerge when you engage diplomatically? These questions apply to marriage too, don't they? How many people get married without really knowing the answers to these questions? Divorce sucks. Losing a friend or injuring a family member in a business venture sucks too. If you're seeing a consistent lack of harmony that is affecting your efforts, and you haven't even proven a Product-Market Fit, then you're partnership probably isn't going to survive the rigors of pleasing shareholders, serving customers, and leading employees. It might be time to cut your losses.

Understanding the pros and cons of co-founding with family and friends.

There are both pros and cons to founding a business with friends or family. All of the advice that I’ve tried to provide here already, applies to creating a business with friends or family, but perhaps with much greater urgency. Knowing and caring about the motivations of others, and how to align incentives, might come more easily when they are among family or friends. Going the extra mile to meet a common goal might be facilitated in a situation characterized as a “labor of love.” If there is a high degree of “trust,” then that can certainly be a pro, but it can also be a “con” if contributions are not well understood or fully appreciated. In other words, I’ve seen and experienced this working out really well, but equally working out very poorly. In effect, it seems to work out on the extreme side of either good or bad. I would say that you really need to examine the relationship when considering a business with a friend or family member. Have you had disagreements before? If so, how did you move through them? If not, just wait until you’re in business together because disagreements will come. I’d rather have had tons of prior, intense debate with a friend or family member that ended on good terms than enter business with a friend or family member who has always been amiable and agreeable in limited, familial settings. I’ve created businesses with friends. I’ve created businesses with my family. If you’re considering engaging in business with a friend or family member, I would say that prior experience with startup principles in a similar line of business - within the last 10 years - among all co-founders is highly desireable. Everyone should be clear of illustions and have moved beyond 20th Century theory for business creation. All of that said, I have to advise that the most productive outcome that I experienced with a co-founder in a tech startup was someone with whom we shared little social interaction outside the office. We were cordial and respectful to one another. We knew what motivated the other, certainly. But if we had a beer together, it was always in a business context. In fact, that only changed after we sold the company together for eight figures.